Buildings, residences, structures make up the fabric of a city. For trailblazing architects like Jason Buensalido, the art of building design isn’t just about the built environment. It’s also about culture.

But the application of that concept in the country f lies in the face of the Filipino’s reality.

“Why will people care about culture when they care about just looking for money, so they can buy food for the day? Since that’s majority of the Filipinos, the developers for that majority will also not care about ‘self-actualization’ ‘culture’ . . .”

In a third-world country, millions of people know zip about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, precisely for the reasons Jason illustrated. “That was the reason for me in putting up the firm; to contribute in a positive way to the development and the moving forward of our culture in a contemporary way; and to look for opportunities for new expressions of architecture.”

The Building Blocks

To honor the cultural nuances of the Philippines’ built environment has been at the forefront of Jason’s trade. His vocation, really. It held a powerful persuasion even while he was a student at the University of Santo Tomas, where he says his love for Philippine culture and architecture sprang. And where he and a few other students came up with the winning design for the Nayong Pilipino redesign competition in 2002. A first of many wins Jason would eventually receive years later.

The string of competitions, however, weren’t about nabbing the top prize. The goal wasn’t to edge out the competition, which were usually the biggest architectural firms in the country.

“Each competition that we were winning was to kind of to contribute to the development of culture — to the meaning of Philippine architecture.”

In 2006, when Jason put up Buensalido Architects, their competition entries were more frequent. Jason explains they had more time then because of few clients, as is the case for most startups. In 2009, they landed the top prize in the Pinakamagandang Bahay sa Balat ng Lupa for their green house, which featured a “secondary skin” future owners could personalize. Also in 2009, the team received a special nod from the Bahay Pinoy Bamboo Design Competition for innovation in their modern bamboo dwelling.

For Jason and his team, the competitions were about showcasing new ideas, pushing the conversation toward the Filipino identity in structural design. To see the country’s culture represented in the buildings and homes and cities that surround communities, the way Balinese culture and Hinduism are evident in every structure in Indonesia and the way intricate work and prominent domes and arches adorn buildings in Dubai.

The series of recognition from those competitions did more than highlight the near-absence of Filipino design in Philippine architecture. It also opened up opportunities for Buensalido Architects, allowing them to work on more projects.

So the “laboratory” of building design and construction grew. It has grown to a point where its principal architect and founder recognized the conflict between commerce and commitment.

“If you keep on saying ‘yes’ to clients who are not necessarily aligned to what you want to achieve, then you will attract the same kind of clients. . . you will lose what you’re trying to achieve. So I started saying ‘no’ — even if that meant losing business and getting hungry.”

No Cookie Cutters

The innovative mind succeeds when the big risks are carefully considered — and then taken. In Jason’s case, he has two significant ones, so far.

One involved quitting a job at an architectural firm to focus on an entry for the CCP Design District Masterplan, which he and his team won, while still courting his now wife, architect Nikki-Boncan Buensalido, the firm’s design ambassador and VP. The other is saying “no” to big projects that didn’t match the Buensalido Architects mission.

The Law of Attraction worked for Jason, and Buensalido Architects began welcoming like-minded people; clients who were not just open to new ideas but also receptive to inventive solutions. After all, what is architecture if not solving problems.

And one of the biggest problems, where Maslow’s bottom tier is concerned, is shelter — housing that’s affordable but still attractive and absolutely responsive to its environment.

“We intentionally reach out to developers that do housing (low-cost, medium range), ‘cause we can make a maximum positive impact with developments like that. Because we’re talking about 1,000 homes and five people to a home; that’s 5,000 people to a project. . . part of our mission is to also affect lives positively as much as we possible.”

Every project at Buensalido Architects marries the art and science of the craft; every architect spends time understanding the client, the environment to be built on, and the community that’s going to have a connection with the building or structure.

But sometimes, the client is in the dark.

Pushing the Boundaries

“Our job as designers is, really, to convert architecture into space; to manifest in architecture the values you already know, supposedly. And if you don’t know those values, then we can’t do that job for you. And then you’re always gonna say, ‘Ah, I don’t really feel what you designed for me.’ So I design something (else). ‘Hmmm, I don’t really feel what you designed for me.’ Then I have to change it. And then it’s a never ending thing because (the client) never defined their values or who they are collectively, from the start.”

When that happens, Buensalido Architects collaborates with another creative team: Design for Tomorrow.

“We work together well because I respect Ric and the value of what he does; and he understands the value of what we do also. We’re not just your cookie-cutter architect. If the project, which he just so happens to handle first, requires something out-of-the-box, that connects with identity in a more accurate way, then he calls on us.”

Jason has known Design for Tomorrow’s chief strategist and creative director since Buensalido Architects started, referring to Ric Gindap as one of his mentors. Since DFT’s founding, the two creative forces have worked on many projects.

Next year, that collaborative work will be manifested in Buensalido Architects’ branding and the upcoming monograph celebrating 15 years of B+A. Jason shares with the organization’s growth comes the need for further structure and a pivot away from attracting clients by “being loud” to developing a new identity while honoring their roots and building on the future.

The art and science of architecture thrives within this “laboratory,” where the experienced and the young forge ahead with concepts that push the craft. At the helm, Jason continues to inspire, compel, and drive his team to deliver awe-inspiring architecture that also represents the distinct identity of the Filipino–all key elements at the heart of Buensalido Architects’ branding.

—

A Selection of Buensalido+Architects x DFT Collaborations

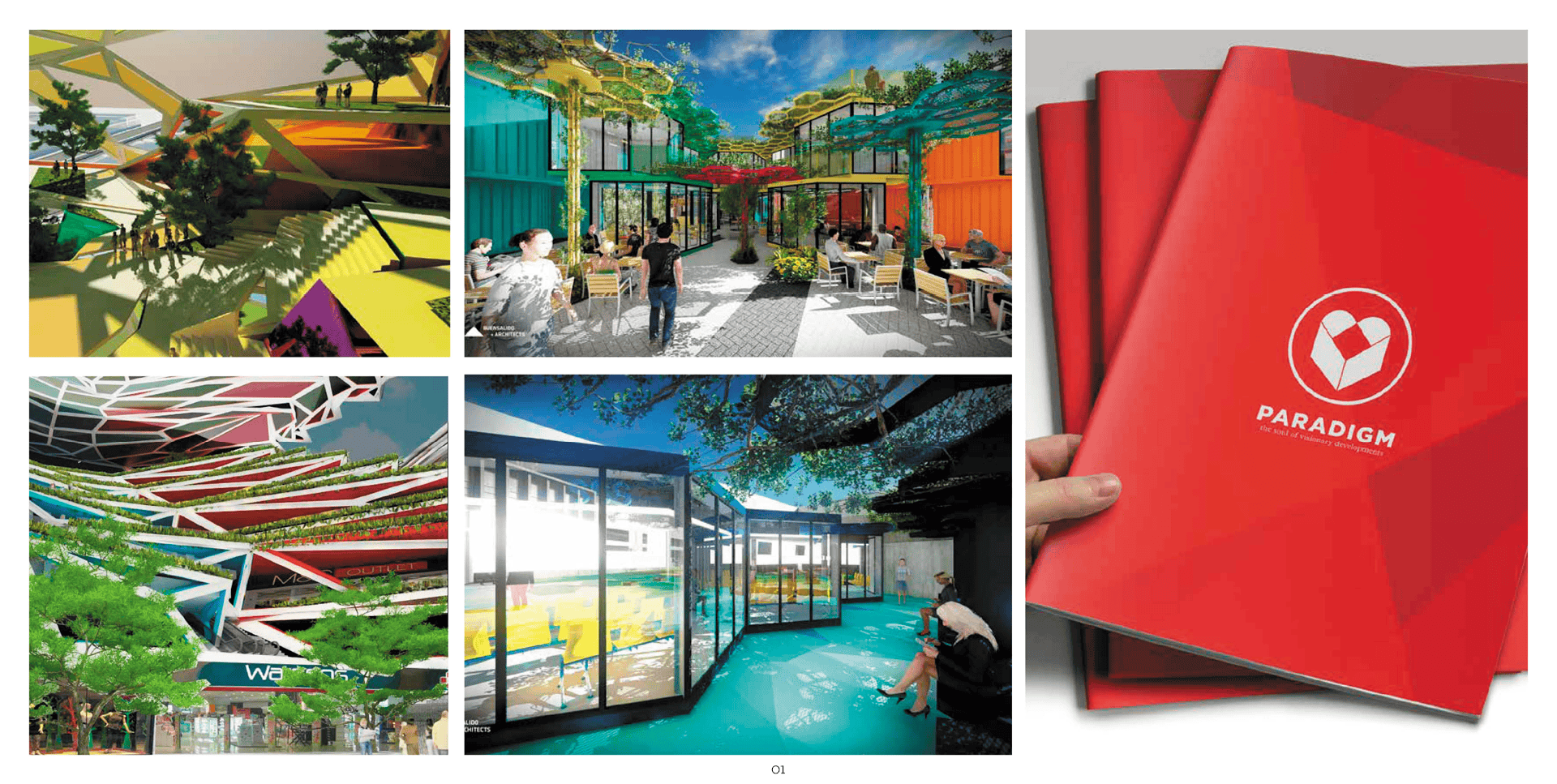

(01) Paradigm Development – DFT provided a brand identity and design framework which was translated by B+A

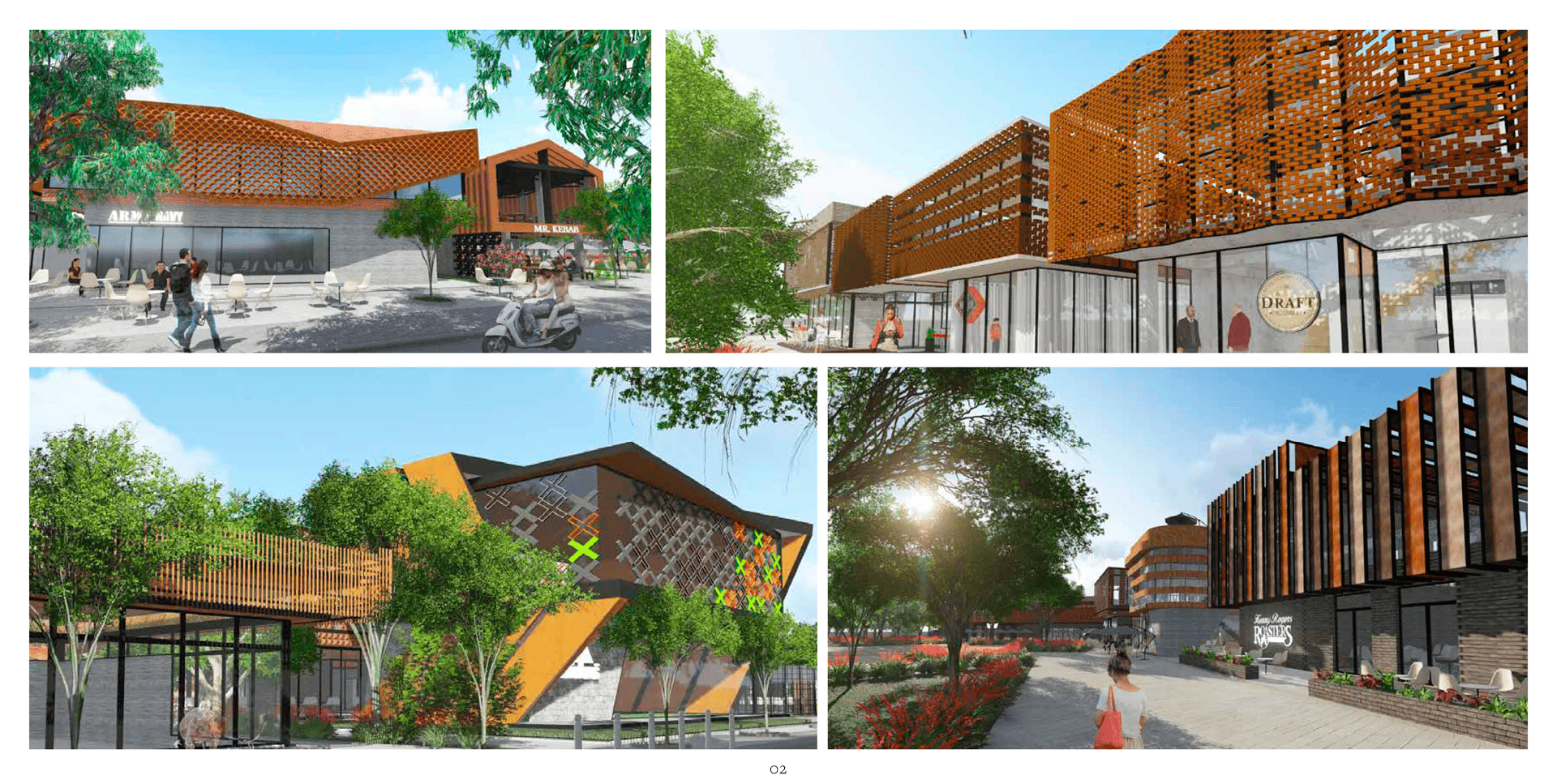

(02) Altea – DFT challenged B+A to modernize the local building vocabularies of Bulacan for a well-curated retail destination.

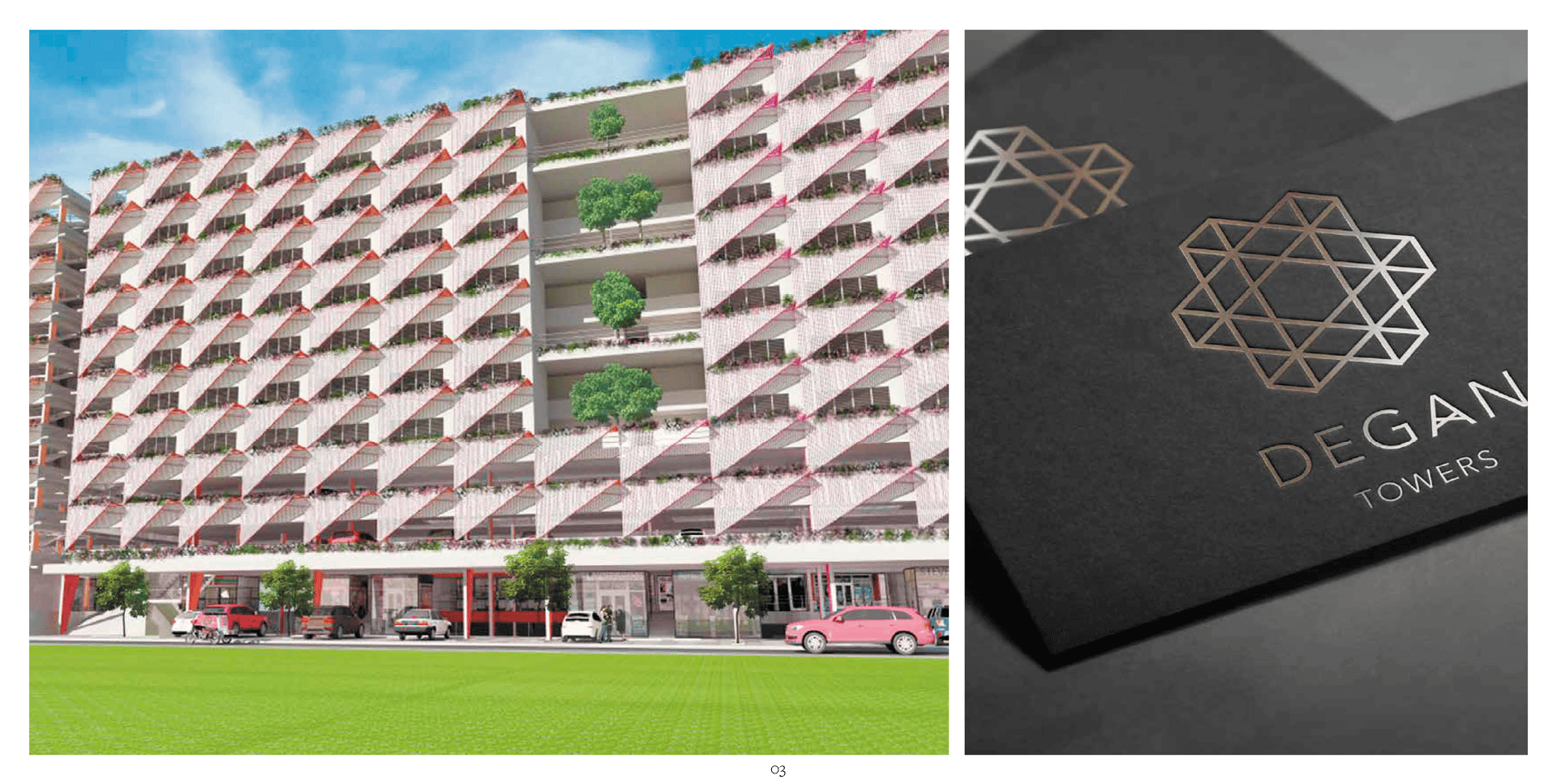

(03) Degan Towers – B+A and DFT collaborated for the identity of a legacy development project in Mandaluyong City.

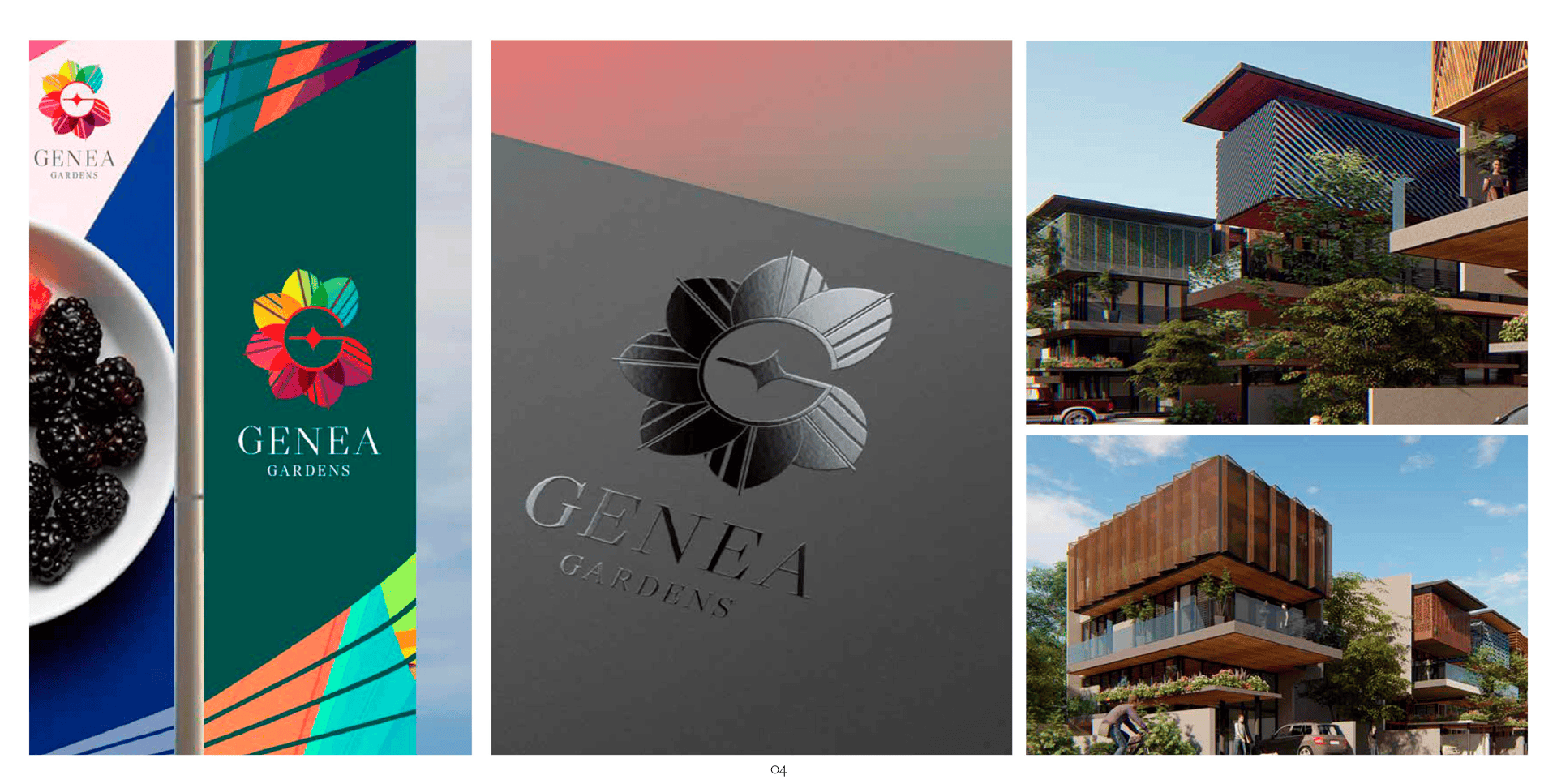

(04) Genea Gardens – DFT articulated the vision of the project and B+A developed an architectural framework that can be personalized and reflective of the spirit of the brand.

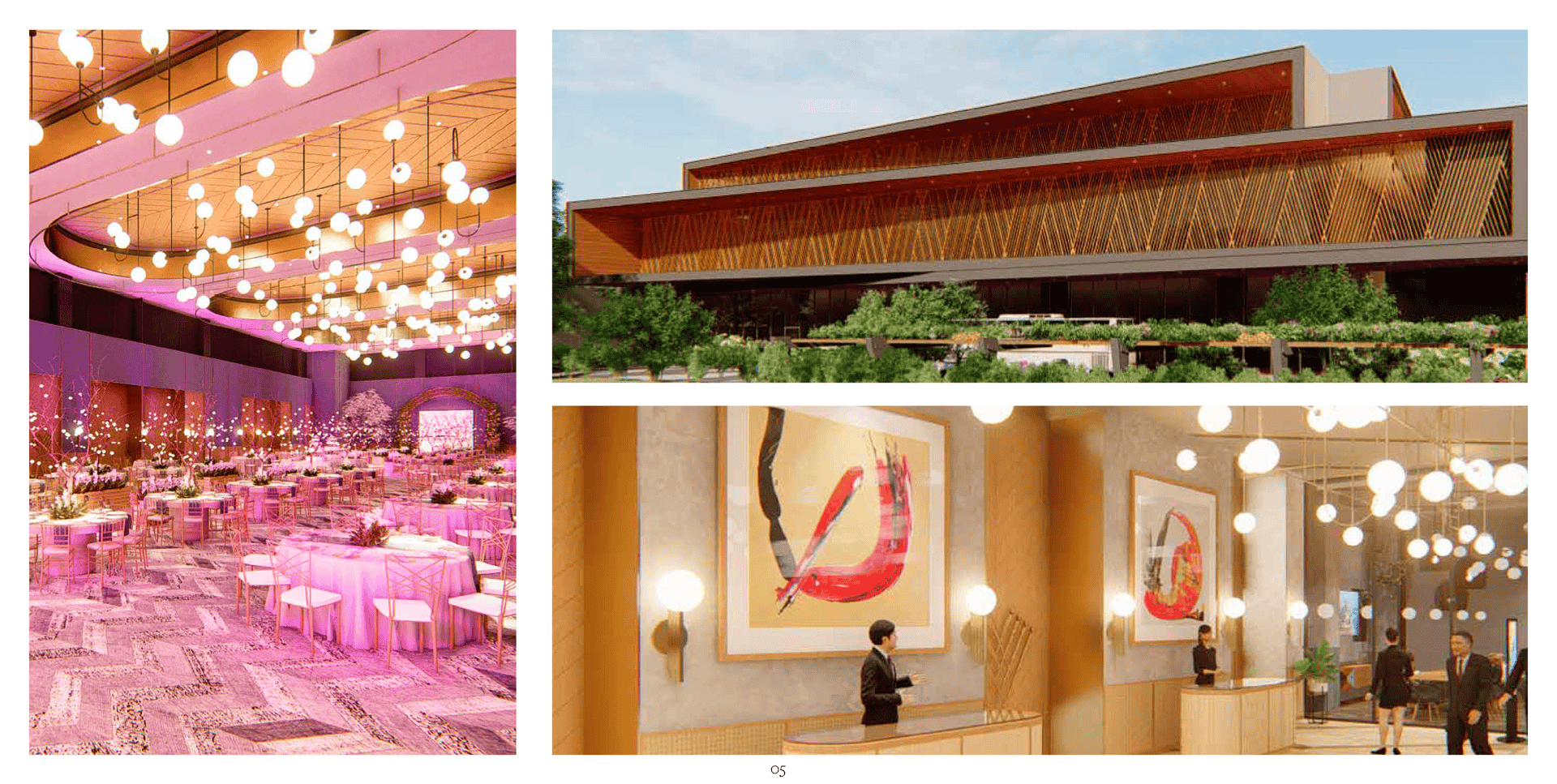

(05) Convention Center – A landmark project in Western Visayas where DFT and B+A cross pollinated branding/identity environments, spatial design, and experiences.

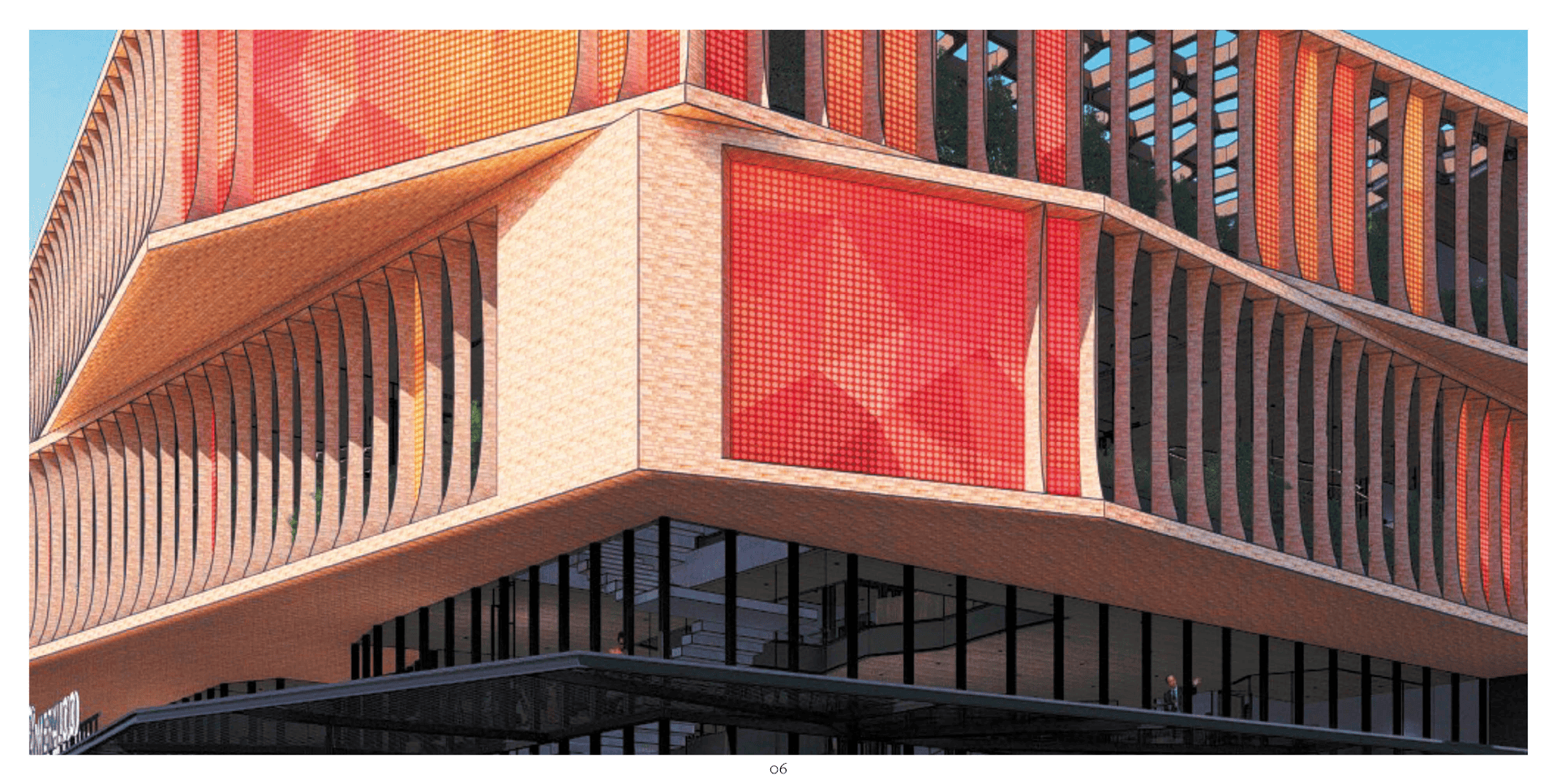

(06) DFT provided an experiential framework and a manifesto reflecting the use of corporate and commercial spaces founded on interaction, empathy, well being, and civic pride. B+A translated this into architecture, interior design, and sustainability features.

Writer Jen Tagasa

Photography and Concept Images Buensalido+Architects Team

Date Published October 22, 2021